Cetaceans (whales and dolphins) are marine mammals that have adapted entirely to the marine environment. They live, feed, give birth and suckle their offspring in water but they have to come up to the surface for breathing: they breathe atmospheric air with lungs as all mammals do.

Cetaceans never sleep but relax in turn the two halfs of their brains: one half is resting while the other half controls the tasks of breathing and navigating. Their nostrils (1 or 2 ‘blowholes’, depending on the species) have moved to the top of their head through evolution of life in water. Their loud exhaling at the surface is full of vapour and shoots upwards in a column, seemingly of water, as vapour condenses as it cools in the air which is colder than the animal´s body. This column may be visible from some miles away.

Sperm whale, blowhole

Cuvier’s beaked whale, blowhole

Striped dolphin, blowhole

In the Mediterranean, 22 cetacean species both permanent residents and visitors or vagrants have been recorded so far. In the Greek waters, 13 species have been recorded to the present time: 8 permanent residents and 5 visitors.

For more information see www.accobams.org

See also our photo gallery

Main threats:

Cetaceans are threatened by food shortage due to over-fishing, by pollution, death through accidental catches in fishing gear (mainly in illegal drift nets), deliberate killing because of the damage they cause to fishing gear (dolphins) and noise pollution: noise from boat traffic and under-water military exercises with the use of sonars interacts with the orientation system several species have, causing disorientation and stranding. This orientation system, also a sort of sonar in the front of their head, allows cetaceans to locate their food, other animals and obstacles.

All cetaceans are strictly protected by the Habitats Directive of the EU and by Greek legislation. Additionally, they are protected by several international conventions.

What we have done:

We organized the long-term recording of cetaceans in the Ionian, in collaboration with fishermen, other local people, visitors and cetacean experts. More specifically, the fishermen on board the swordfish vessels of Kefalonia recorded daily over six years their observations of cetaceans and took pictures when possible (1990 – 1995).

We have recorded eight and possibly nine different cetacean species to the present time: from dolphins and beaked whales to extremely large marine mammals like sperm whales and fin whales, which grow to 18 and 27 metres in length respectively and live mainly in the deep open waters off the western coasts of the Ionian islands.

The cetacean diversity in the Ionian Sea, which up to the present time contains almost half of the Mediterranean’s species, is certainly exceptional.

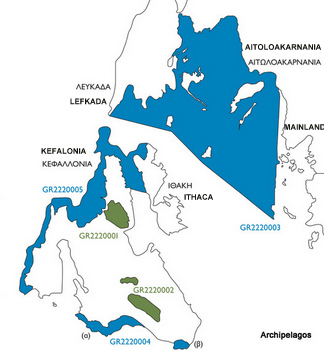

Based on these (and other) data that emphasized the need to protect the marine area off the western coasts of Kefalonia, in 2002 these regions were included in the National Catalogue of NATURA sites as a new, third marine NATURA site in the central Ionian Sea under the code GR2220005.

The so-called NATURA 2000 sites are ecologically important areas, both marine and terrestrial, which are to become a network of protected areas.

The cetacean species we have recorded are listed below along with a short description of each species and details of our observations.

1. Short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis)

The species can reach up to 2 metres of length and its coloration is quite complex: the back is black or dark grey. The area below is light yellow-beige in the front and light grey in the back. Below this part, the belly is white. Common dolphins live in both shallow and deep waters and feed on sardines, anchovies, shads and less on squid. Despite its name, the species is no longer common in the Mediterranean: it has disappeared from the Adriatic Sea and has become fairly rare in the western Mediterranean.

Each dolphin has a different colouration on the dorsal fin, large or small light patches etc. which, together with possible scars make it recognizable (picture below). This is how all dolphin species are individually photoidentified.

During our surveys, we registered common dolphins several times.

In Greece, the common dolphin can be found in several places in the Aegean and the Ionian Seas. In the late 90´s, a resident population of at least 150 and possibly 300 common dolphins lived and reproduced in the Inner Ionian Archipelago (studies: Tethys Institute, Milano, Italy). They lived with the coastal bottlenose dolphins in the same area, ‘sympatrically’, a rather rare event. During the past decade, a rapid decline of the population was registered: from 150 animals photoidentified only 15 were found again in 2007. This fact was attributed to food shortage due to over-fishing by large trawlers and triggered fears for a collapse of the population. In recent years however, there are indications that the animals left the area and are now rather dispersed in the open waters of the Ionian Sea.

2. Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

This dolphin species, our well-known ‘Flipper’, can reach a length of up to 3,5 metres and has a uniform dark grey colour on the back and light grey colour on the belly. It lives in coastal waters feeding on eels, sardines, anchovies and also red mullets, hakes and octopus or squid.

In autumn 1994, on one of our monk seal surveys, we recorded two very young (less than a year old) bottlenose dolphins off Northern Ithaca, together with one or two adult animals. This fact, along with data of the Tethys Institute, proves that the species is actively reproducing in the central Ionian Sea.

3. Striped dolphin (Stenella coeruloalba)

This dolphin species is a pelagic species living in fairly deep waters and feeding on small fish and squid. It can reach a length of up to 2 metres and is dark grey on its back with a nuance of blue. The lateral zone is light grey and the belly is white. A fine distinct black stripe starts from the eye and stretches towards the genital part of the belly (thus the name striped dolphin). It is the most common dolphin species in the Mediterranean.

In summer 1995, during a survey for monk seals, we encountered a herd of about 50 striped dolphins in the western part of the gulf of Myrtos in NW. Kefalonia. The animals were playing with our inflatable for about two hours and came up in front of our bow, almost to reach by hand. They stayed in this area even after we left as we had to do our work…

4. Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus)

This dolphin species has a length of up to 4 metres. Unlike the other dolphin species, it has no beak. Its colouration is light grey when newborn and it becomes darker with age. However, the tooth scars from fights with other animals are of very light colour and the head may sometimes appear white.

The species is highly pelagic and lives mostly far off shore feeding on cephalopods (squid); thus, an encounter with a Risso‘s dolphin is rather a rare event.

Vassilis Tsarnas, however, a friend of our NGO, photographed at least 4 such dolphins only about 500 metres off Sarakiniko on the eastern coast of the island of Euboea as can be seen in the picture (1998).

As far as we know, the first documentation of the presence of Risso‘s dolphins in the central Ionian Sea derives from observations and pictures taken and brought to us by Nikolas Voutsinas and his wife Alexandra Voutsina, fishers participating in our network for reporting cetacean sightings, who were fishing swordfish off the western coasts of Kefalonia (picture below).

5. Cuviers’ beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris)

This species is strictly pelagic diving up to 3000 metres and feeding on squid at these depths. It can grow more than 6 m long and its colour is variable: males are usually dark grey to olive green but old specimen may be white. Females are dark grey to grey-brown or light reddish-brown. Cuviers’ beaked whales have lost their teeth during evolution and only the adult males have one pair of small teeth in their lower jaw.

From 1989 through to 1995, Cuviers’ beaked whales were regularly registered in the gulf of Myrtos in NW. Kefalonia by our network of fishermen fishing swordfish at high seas.

Unfortunately, most swordfish boats were later either sold or withdrawn from fishing and the registration of cetaceans by the fishermen had to stop.

In August 1989, while fishing with drift nets (the so-called ‘walls of death’) was still common in the Ionian Sea, mainly by Italian boats fishing swordfish and tuna, a Cuviers’ beaked whale got caught in drift nets. A fisherman from the island of Lefkada liberated it from the nets but the animal was hurt and had to stay at the surface in order to breathe. The intense sun burnt the soft skin of the animal causing blisters and burns – just like in humans. Lambros Tselentis, a professional fisherman from Fiskardo, Kefalonia, saved it by pouring buckets of seawater on its back. A few days later he saw the whale again: he could recognize it because of its wounds and burnt skin. The whale had survived and had recovered substantially.

In 1993, two juvenile beaked whales, a male and a female of 5 metres length most probably hit by a virus infection, became stranded in a bay in S. Kefalonia and died there.

In 1997, we registered at least 7 dead beaked whales in the central Ionian Sea. This event coincided with a mass stranding of the species in SW. Peloponnese, caused by disorientation through the sonar frequencies used in military exercises at that time.

6. False killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens)

The species is extremely rare in the Mediterranean: observations do not exceed 30-35 cases for the entire area. It feeds on big fish such as tuna, barracuda, bonitos but also squid. False killer whales can reach 5-6 metres in length and their colour is uniform black or dark grey all over the body and the fins.

In Greece, only one stranding of a false killer whale had been registered in 1993 in the gulf of Argos, E. Peloponnese.

But in 1995, we saw by chance two false killer whales together off the Assos peninsula in ΝW. Kefalonia.

Our photographs are really poor due to the conditions in our small inflatable. But they are still documents of an extraordinary event:

Our observation is the first observation of living false killer whales in Greek waters!

7. Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus)

The sperm whale is the third largest whale on earth and the males can reach 18 metres in length. They dive up to 2,000 metres deep and feed on giant squid in these depths.Their most distinctive feature is their almost rectangular head with the blowhole at the left part of the head and not in the middle as in other species: so their breath is not vertical but goes sideways to the left as can be seen in the picture.

In Greece, there is a resident reproducing population of sperm whales along the western coasts of the Ionian islands and the southwestern coast of Crete. The NGO «Pelagos Cetacean Research Institute» is carrying out special studies on this population and has identified about 200 individuals.

Sperm whale observations have been reported several times in the central Ionian Sea through our network. In the early 2000’s, a sperm whale was stranded in a bay in NW. Zakynthos.

8. Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

The fin whale is the second largest whale on earth after the blue whale, reaching up to 27 metres in length. Its colouration varies between silvery-grey and dark grey on the back and is white on the belly and the lower part of the lateral fins with a fairly sudden change. Instead of teeth, the fin whale has a series of baleens through which it filters the zooplankton (the so-called krill) and small fish from the water taken into its huge mouth (picture right).

Fin whales, a pelagic species living in the open sea, are permanent residents in the Mediterranean: a thriving population lives and reproduces in the waters between Corse, Italy and France where an extended whale sanctuary has been established.

In Greece, fin whales live mainly in the deep waters off the western coasts of the Ionian islands. They are often present along the Hellenic Trench (Ionian Islands, gulf of Messinia, islands of Kythira/Antikythira and the Libyan Sea south of Crete). Their presence in the enclosed basin of the Aegean Sea is rather rare.

However, from time to time fin whales do enter the shallow Inner Ionian Archipelago: on the small island of Kastos, a few hundred metres off the mainland, we found the skeletons of two fin whales that had become stranded there in the past, one in the 70‘s and one some decades before; the huge head of the whale gives an idea of the animal’s size (picture right).

In May 2008 we carried out an autopsy of a dead 15-metre long juvenile fin whale that was found off the port of Sami in eastern Kefalonia; it had been shot in the neck using a heavy weapon. We presume the whale was caught in drift nets –usually of Italian vessels that still fish far off shore with this illegal gear– and the fishermen killed the animal in an attempt to save their equipment…

9. Killer whale (Orcinus orca)

Orcas are present in the Mediterranean, though encounters are rare. The orca is a pelagic species and it usually does not approach the coasts. The animals have a distinct black and white colouration and can reach 9 metres in length. They are top predators hunting big fish, seals, etc.

Observations concentrate in the area of the Straits of Gibraltar (pictures) but sporadic sightings have also been reported from the eastern Mediterranean Basin, from Israel and from Malta, for instance. One orca observation was recorded in the open Ionian Sea as well, approximately in the centre slightly further to the west. The species is not included in the cetacean species of Greek waters because the observation was made outside the Greek Exclusive Economic Zone as territories are divided on the basis of administrative -and not of biological/ecological- criteria. In any case, it is very probable that orcas do enter the Greek waters since they migrate over huge distances and they are not aware of national borders.

Fishermen who participated in our cetacean observation network have reported an observation of a herd of about 10 orcas around their swordfish boat in the late 80’s off cape Gero-Gombos, the southwestern tip of Kefalonia.

But since no pictures were taken the event cannot be registered as an official observation of orcas in Greece.