Distribution

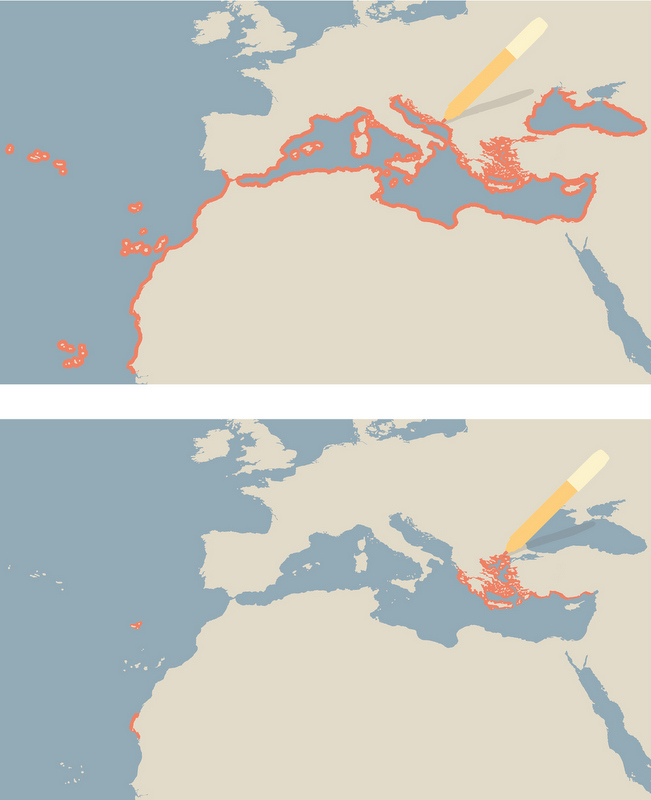

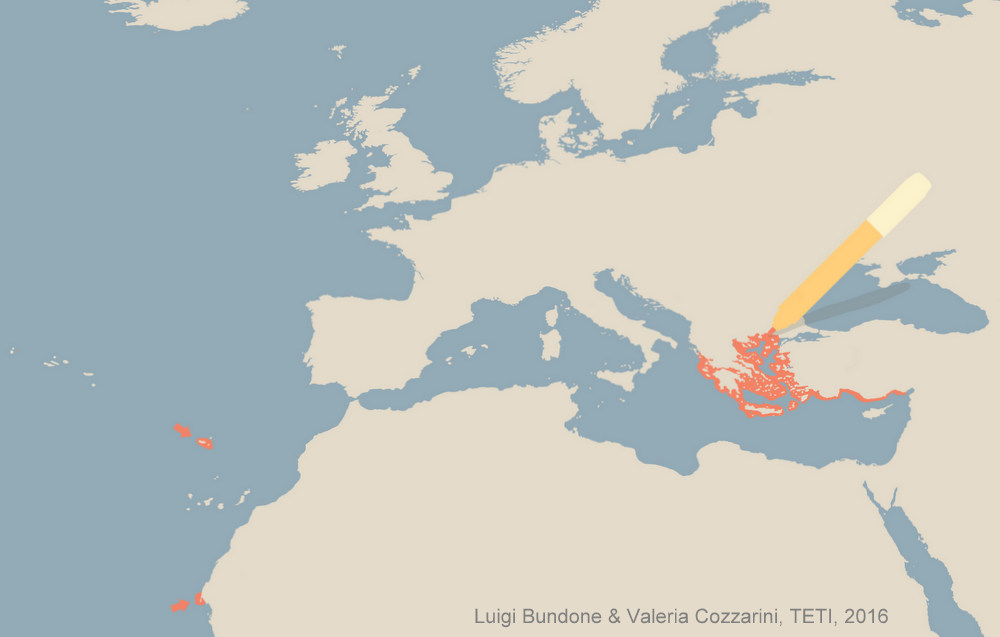

The total population of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) that remains today is estimated to consist of approximately 700 individuals, of which about 400 live in the Mediterranean basin.

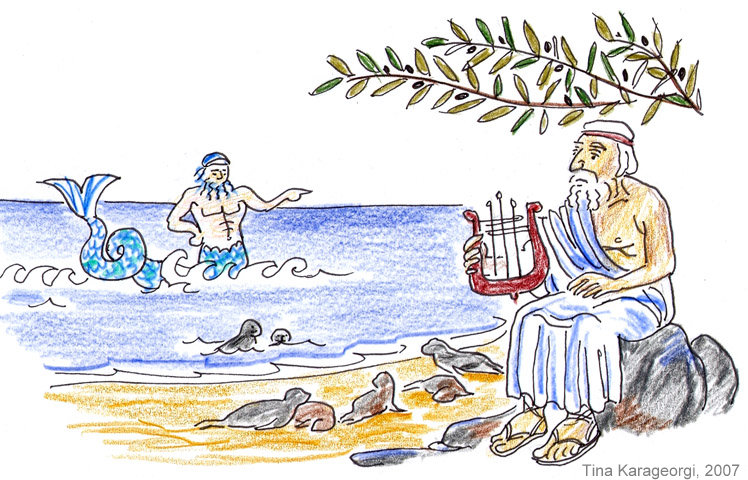

Its former distribution range extended throughout the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Atlantic coasts of NW Africa including the Canary islands, Madeira and the Azores. Homer describes vast herds of seals lying on the beaches, while Proteus, a sea god, would daily come out of the sea counting them in groups.

When thro’ the Zone of heav’n the mounted sun

Hath journeye’d half, and half remains to run;

The Seer, while Zephyrus curl the swelling deep,

Basks on the breezy shore, in grateful sleep,

His oozy limbs. Emerging from the wave,

The Phocae swift surround his rocky cave,

Frequent and full…

Odyssey, Book IV, 404-409

Today, however, these charming animals have disappeared from  extensive regions of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

extensive regions of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

In some Mediterranean areas only a handful still exist.

Actively reproducing monk seal populations are found mainly in Greece and Turkey (approximately 350) as also in Mauritania (330 photo-identified animals) and Madeira (ca. 40).

Apart of these well-known populations, the species is considered extinct or of unknown status in large parts of its former range.

Unless effective measures are taken promptly in the entire Mediterranean, the monk seal will disappear altogether in the next couple of decades, and our sole reminder of them will be legends and fairy tales.

Why is the Mediterranean monk seal disappearing?

During the Roman Empire, when seals were shown even in circus games, monk seal numbers were significantly reduced through massive hunting. Heavy hunting continued in the Atlantic Ocean by the Spanish and Portuguese in the 15thand 16th centuries, mainly for commercial reasons.

mainly for commercial reasons.

In the Mediterranean Basin, the monk seal was hunted for its skin (belts and shoes) and its fat (lighting and soap) up to the ´50s. Its fur, however, was never used on a large scale for commercial purposes.

In most Mediterranean countries, fishermen have always regarded seals as enemies and deliberately killed them because of damage incurred to their fishing gear and catch, as the seals ate the fish caught in their nets (and, of course, still do). The damage done by seals is not negligible.

Yet, so many centuries of seal hunting and deliberate killings did not drive the species to extinction. The decline in their population rapidly increased after World War II.

What is to blame?

From the map showing the monk seal’s present distribution

it can be seen that seals have disappeared from the

particularly densely populated areas of the northwestern

and southeastern Mediterranean: that is where man’s impact

has been massive…

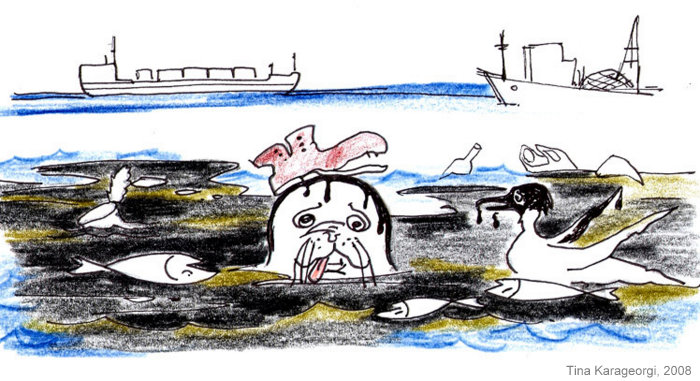

Marine pollution: oil spills ruin marine caves, various toxic substances (heavy metals, pesticides, sewage from harbours, towns and industry, etc.) poison the fish – the seal’s food and ours too.

poison the fish – the seal’s food and ours too.

The impact (impaired functioning of the immune, reproductive, nervous systems, etc.) is not immediately obvious since it takes years for the effects to appear.

And they will also manifest themselves in us humans if only later because we eat less fish.

Over-fishing both by professionals and amateurs with ultra modern means that scour the sea, often illegally with poisons and dynamite or simply by leaving the nets in the sea for days.

or simply by leaving the nets in the sea for days.

Eventually, both fishers and seals will be looking into the same empty net.

Thus, slowly but surely, as the monk seal disappears so does the occupation of the traditional coastal fishermen which have always respected the sea. We then wonder why fish is so expensive…

The ever increasing disturbance by man: Yachts, ships, boats and jet skis approach even the most remote islands and the most isolated sea caves: monk seals are driven away from their last resorts.  Mothers may miscarry if frightened, or may abandon their helpless pups.

Mothers may miscarry if frightened, or may abandon their helpless pups.

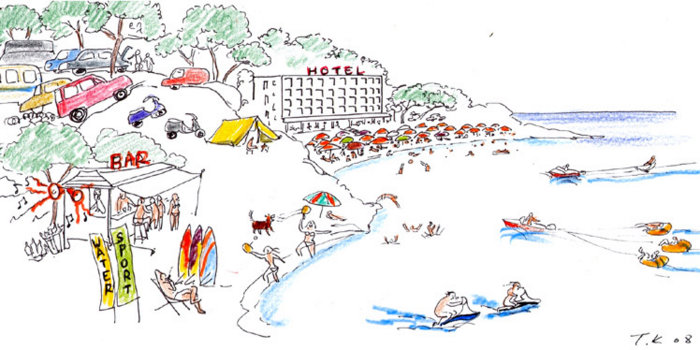

And, finally, the continual and irreversible destruction of the monk seal’s habitats: factories, ports, streets, hotels and taverns right at the seaside appear everywhere without any planning. Where should the monk seals go?

This is indeed the most severe threat in the long run: even if persecution is immediately stopped throughout the monk seal’s range –and measures to curtail it are already well under way– the monk seal will not survive without safe refuges for resting and reproduction.

The Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus, is the world´s rarest seal species and the total population is estimated to consist of approximately 700 individuals. The species is classified by the IUCN as Endangered.

National legislation: most Mediterranean countries have included the monk seal in laws for the protection of their rare/endangered species and in regulations regarding hunting or fishing. In Greece, for instance, Presidential Decree 67/1981 lists the monk seal among the protected species. In Italy is protected by law No.157/1992 regulating the protection of wild fauna and hunting activity.

EU legislation: In the EU Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 “On the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora”) the monk seal is listed in Annex II (list of species for which Special Areas of Conservation or SACs are required) as one of the “priority species” and also in Annex IV (list of species for which full protection is required, irrespectively of whether their populations are found within established SACs or not.

Furthermore, the Mediterranean monk seal is listed in the following international Conventions:

- CITES, 1973: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

-

SPA/BD Protocol, 1985 (Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Mediterranean Biological Diversity, within the Barcelona Convention for Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution, 1979). The monk seal is included in Annex II of the Protocol, in which the species listed are classified as threatened and appropriate measures for their conservation and management are needed. The Protocol also foresees a specific Action Plan for each of the species listed.

-

Bonn Convention, 1979: Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. The monk seal is included in Annex I (protection of the species´ habitats) and Annex II (need for international agreements).

- Bern Convention, 1979: Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. The monk seal is included among the species of Annex II: any killing or disturbance of the species listed is prohibited and the designation of special areas for their conservation is required.

- CBD Convention, 1992: Rio Convention on Biodiversity

-

African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1968. The monk seal is included in the list of species of Class A for which any killing or withdrawal from nature is prohibited with the exception of scientific purposes or national interest.

The Mediterranean monk seal is also listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act and designated as depleted under the US Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

What we have done:

In the Ionian Sea, western Greece, we implemented a holistic approach from the very beginning of our conservation activities back in 1985 and for the first time ever at international level: in addition to basic parameters such as the study of the seal population and its habitats, environmental education and public awareness, etc., we took into consideration additional parameters that had never been studied before:

For the first time ever, the seal damage to gear and catch was systematically recorded with the help and co-operation of our friends, the fishermen, and the degree of this damage was established scientifically. The interaction between seals and fishermen (which always led to the killing of seals in earlier years) was studied, and proposals for mitigating this crucial problem were elaborated. Based on our results, interaction with fisheries was identified as one main threat to the species in Greece.

For the first time ever, a network with the participation of local people and tourists for the collection and evaluation of seal sightings was created, which has been operating since 1985 without interruption.

For the first time ever, chemical analyses were conducted of seawater pollution and contamination of fish, which are food for both seals and humans. We concluded that pollution is not an acute threat to the monk seals here. [see Marine Pollution]

We also promoted the establishment of Marine Protected Areas wherever and whenever possible: in 2000-2002, we provided the scientific documentation for an additional marine NATURA 2000 site in the central Ionian Sea. As a result, a third marine NATURA site was included in the National Catalogue of NATURA sites in Greece.

This integrated strategy, elaborated to a full document with the co-operation of the NGO MOm in 1994, was later adopted by the Greek Ministry of the Environment and the EU, and its most important points are now the basis for all conservation activities for the monk seal in Greece.

Later, and especially after the establishment of Archipelagos Italia, we expanded our monk seal activities: we studied habitat availability in Israel, Montenegro and Apulia/Southern Italy; we reviewed reported sightings throughout the species´ former distribution throughout the Mediterranean Sea; we studied the monk seal’s diet; and we carried out photo-identification projects in Croatia and Israel.